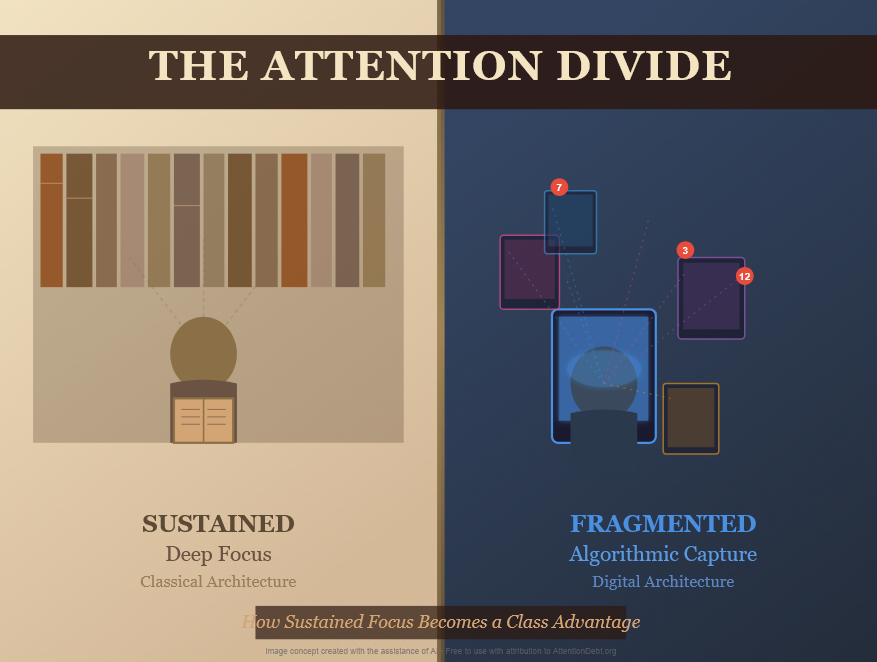

The Attention Divide: How Sustained Focus Is Becoming a Class Advantage

Important Context & Disclaimers

On Language and Frameworks

This article attempts to create language for phenomena we’re still learning to observe and describe. Terms like ”attention debt,” ”attention bankruptcy,” ”cognitive stratification,” and ”attention solvency” are analytical frameworks—tools for thinking about complex developmental and societal patterns—not established diagnostic categories or scientific consensus.

On Attribution and Mechanism

This article describes systemic patterns and structural incentives, not individual intent. When discussing technology companies or market dynamics, the analysis focuses on observable patterns and structural incentives, not moral judgments about specific people or organizations.

On Scientific Claims

Research on attention development is evolving. Claims represent current understanding based on available research, not immutable facts. This is not medical advice and should not be interpreted as diagnosis or treatment recommendation.

This Is Not: A moral judgment, a diagnosis, a claim that technology is inherently harmful, or an attack on specific companies.

This Is: An attempt to name observable patterns, a framework for understanding developmental environments, and a call for public infrastructure to make attention preservation accessible.

Steve Jobs limited his children’s technology use at home.

In an interview published in the New York Times in 2014, reporter Nick Bilton recounted a dinner in 2010, shortly after the iPad’s launch, where Jobs said his children hadn’t used it yet. ”We limit how much technology our kids use at home,” Jobs explained.

This was the man who created the device. Who understood its psychological impact. Who built a company that would become the world’s most valuable by selling these devices to families everywhere.

And he kept his own children’s use carefully limited.

The pattern extends beyond Jobs. For example, a 2018 survey found that many Silicon Valley executives send their children to schools with limited or no screen use. Waldorf schools—where digital devices are restricted, where education emphasizes physical materials and sustained attention activities—have substantial waiting lists in Palo Alto and Cupertino, the heart of tech innovation.

Those closest to understanding how attention-capture technology works often choose to limit their own families’ exposure to it during childhood.

This pattern raises a reasonable question: What do they understand about developmental neuroscience and attention formation that hasn’t yet become common knowledge?

The answer may be simpler and more significant than any conspiracy theory: emerging research suggests that sustained attention capacity is becoming an increasingly valuable cognitive resource. And access to the environmental conditions that support its development during critical childhood periods appears to be stratifying along socioeconomic lines.

This isn’t a story about intentional harm. It’s an analysis of structural incentives playing out at population scale. But the pattern is striking: we may be observing the early formation of what could be described as cognitive stratification—differences in neural architecture development that correlate with childhood socioeconomic circumstances and may compound across generations.

This stratification is occurring during the critical development windows of an entire generation. By the time the pattern becomes fully visible and widely understood, many of those developmental windows will have closed.

The Pattern Emerging In The Data

Once you begin looking for it, the pattern appears in multiple domains.

Research indicates that families with higher incomes are more likely to:

- Employ caregivers who emphasize device-free activities during early childhood

- Choose schools with limited screen integration in early grades

- Invest in activities requiring sustained attention (music lessons, sports, extended reading)

- Structure home environments with designated device-free times and spaces

Meanwhile, schools serving lower-income communities have increasingly adopted comprehensive digital learning programs. Marketed as ”closing the digital divide” and ”preparing students for the future,” these initiatives often mean more screen time during school hours, not less.

The stratification isn’t about access to technology—smartphones are now ubiquitous across income levels. The emerging divide appears to be about access to protection from technology during specific developmental periods that research suggests may be critical for attention architecture formation.

For example, analyses published in 2019 in JAMA Pediatrics found that children from higher-income families averaged significantly lower daily screen time than children from lower-income families, controlling for other factors where possible. The gap was particularly pronounced during early childhood—ages 3-7, the same period developmental neuroscience identifies as potentially critical for sustained attention circuit development.

This creates what we might call a developmental environment gradient: children in different socioeconomic circumstances are experiencing fundamentally different attentional environments during the same developmental windows.

Understanding The Mechanism: How Environment Shapes Architecture

Here’s what developmental neuroscience suggests happens:

Neural pathways develop in response to environmental demands during specific windows of high plasticity. The circuits that support sustained attention appear to develop primarily during early childhood, with a secondary development phase during early adolescence.

When these developmental periods occur in environments that regularly require sustained attention—following long narratives, completing complex projects, engaging in extended conversations—the neural architecture supporting sustained focus appears to develop more robustly.

When these same periods occur in environments dominated by rapid context-switching and algorithmically-optimized stimuli designed to capture attention in short bursts, the developing brain may optimize for different patterns—rapid pattern recognition, parallel information monitoring, quick context-switching—while the circuits supporting extended sustained focus may develop less fully.

Neither outcome is inherently ”better” or ”worse”—they represent adaptation to different environmental conditions. But they create different cognitive capabilities that may be differentially valued in various contexts.

Now consider how socioeconomic status affects the developmental environment:

Higher-resource families can more easily provide:

- Full-time caregiving without reliance on devices for behavioral management

- Educational environments that prioritize sustained attention activities

- Structured activities requiring extended focus

- Protected time and space for undistracted interaction

Lower-resource families face different constraints:

- Devices often serve as necessary childcare tools for overstretched parents

- Schools may have fewer resources for small class sizes and individualized attention

- Less access to expensive attention-intensive activities

- Less buffer against the default algorithmic environment

Middle-income families typically experience:

- Partial protection—some attention-preserving activities, some device-dependent management

- Variable school environments

- Awareness of the issue but limited resources for comprehensive solutions

These aren’t moral judgments about parenting—they’re descriptions of structural constraints. The concern is that these different environments during critical windows may create different developmental outcomes that then compound over time.

The Economic Pattern Nobody’s Named Yet

Language shapes what we can see. We don’t yet have standard terminology for describing how attention capacity intersects with economic opportunity, but the pattern shows up in labor market data.

Occupations requiring extended sustained attention—complex analysis, strategic planning, creative synthesis, any work requiring holding multiple variables in working memory over extended periods—appear to command increasingly premium compensation. This correlation exists even controlling for education level and measured intelligence.

Conversely, work compatible with fragmented attention—task-based gig work, algorithmic completion jobs, positions with frequent interruptions and rapid context-switching—is associated with lower and often declining compensation.

We’re accustomed to thinking about education as the primary mechanism for economic mobility. But emerging research suggests attention capacity in childhood predicts adult economic outcomes with surprising strength—in some longitudinal studies, better than parental income or measured IQ.

If sustained attention capacity is increasingly valuable in the labor market, and if that capacity develops during specific childhood windows, and if access to the environmental conditions supporting that development correlates with family socioeconomic status, then we may be observing the early stages of what could be described as cognitive stratification.

Again, we’re working at the edge of available language here. Terms like ”cognitive stratification” or ”attention-based class formation” don’t appear in standard economic or sociological literature. We’re attempting to name a pattern that may be emerging but doesn’t yet have consensus terminology.

Why This Pattern May Be Self-Reinforcing

If attention capacity increasingly predicts economic outcomes, and economic circumstances affect developmental environments, and developmental environments shape attention capacity during critical windows, then the pattern has a potentially self-reinforcing quality:

Parents with strong sustained attention capacity → Higher earnings in jobs requiring sustained focus → Resources to provide attention-preserving environments for children → Children develop sustained attention capacity → Higher earnings → Resources to preserve next generation’s attention

Parents with compromised sustained attention capacity → Lower earnings in fragmented-attention work → Fewer resources to provide attention-preserving alternatives to default algorithmic environment → Children develop in attention-fragmenting conditions → Compromised sustained attention capacity → Lower earnings → Cycle continues

This is speculation about mechanism, not established fact. But it’s consistent with what we observe about socioeconomic reproduction in general, with the additional concern that we may be discussing neural architecture development rather than just educational or economic opportunity.

If accurate, this pattern would be particularly concerning because neural architecture formed during critical developmental windows may be more difficult to substantially modify later than other aspects of socioeconomic circumstance.

The Challenge For Democratic Participation

Democratic citizenship has cognitive prerequisites we rarely make explicit.

Meaningful civic participation typically depends on:

- Sustained attention through complex policy arguments

- Capacity for critical evaluation of competing claims

- Resistance to emotional manipulation and engagement optimization

- Engagement with important-but-boring civic processes

- Holding multiple perspectives while evaluating evidence

All of this typically depends on sustained attention capacity—not as optional enhancement, but as functional requirement.

If sustained attention capacity becomes unevenly distributed in ways that correlate with socioeconomic status, and if that distribution is determined during childhood developmental windows, then we face a potential structural challenge to democratic participation.

This isn’t a moral claim about any individual’s capacity for citizenship. It’s a systems-level concern: if a substantial portion of the population develops neural architecture optimized for algorithmic engagement rather than sustained policy analysis, how does deliberative democracy function?

We don’t yet have good frameworks for thinking about this. Political science typically addresses barriers to participation—voter ID laws, registration requirements, access to information. It has less developed frameworks for addressing cognitive prerequisites shaped by developmental neuroscience.

But the pattern may be worth taking seriously: if attention capacity required for meaningful democratic participation becomes stratified along socioeconomic lines during critical childhood windows, that represents a new category of challenge to democratic systems.

The Current Moment: Windows Open and Closing

Generation Alpha—children born between 2010 and 2024—are moving through their critical developmental windows right now.

The oldest (born 2010) are fifteen. Their primary developmental window for sustained attention (roughly ages 3-7) occurred between 2013-2017. Their secondary window (roughly ages 11-14) is closing now or has recently closed.

The middle cohort (born around 2017) are eight. They’re exiting their primary window now. Their secondary window opens in a few years.

The youngest (born 2024) are one. Their primary window opens now and extends through 2031.

These aren’t hard boundaries—neural plasticity exists throughout life. But developmental neuroscience suggests these periods matter disproportionately for foundational architecture formation.

For many families, particularly those with fewer economic resources, this is happening without awareness that these periods may be developmentally significant. There’s no widespread public health messaging about attention development windows comparable to messaging about nutrition or vaccination.

By the time the importance of these windows becomes common knowledge—if it does—many will have already passed for the current generation.

Why Market Solutions May Be Insufficient

Standard economic thinking suggests: if attention preservation during critical windows is valuable, markets will provide it. Schools will offer it. Companies will emerge to supply it.

This is happening to some degree. That’s what the tech-restricted schools in Palo Alto represent. That’s what the premium-priced ”analog summer camps” provide. That’s what high-end caregivers who commit to device-free engagement are selling.

But these solutions are systematically expensive. Market incentives optimize for engagement; attention preservation is labor-intensive and costly to scale. The underlying service—sustained human attention from adults with their own strong attention capacity—is itself a scarce resource that’s difficult to scale or automate.

You can’t build an app that effectively trains sustained attention without creating a contradiction—using the app requires device engagement that may fragment the very capacity you’re trying to develop.

You can’t reduce the cost through automation—genuine attention preservation requires human attention from caregivers, which is labor-intensive and therefore expensive.

The result is that market solutions tend to be premium-priced, accessible primarily to families who can afford them. Meanwhile, the default path—the free or low-cost option—is often the algorithmically-optimized environment that may be most likely to fragment attention development.

This creates a potential dynamic where attention preservation functions as a luxury good that becomes more expensive over time as algorithmic optimization improves, rather than a technology that becomes cheaper and more accessible as it matures.

If attention capacity is becoming increasingly economically valuable, and if access to developmental environments supporting its formation is increasingly stratified by family resources, and if market dynamics make attention preservation more expensive rather than less, then market solutions alone may be insufficient to prevent stratification.

Why .org Represents A Different Approach

If the analysis above has any validity—and it should be stress-tested and debated—then access to knowledge about attention development and preservation strategies may need to function as public infrastructure rather than market good.

Consider historical parallels:

Literacy was once a marker of elite status. It became universal not through market forces but through recognition that democratic citizenship requires it. Public education became infrastructure.

Vaccination was once available only to wealthy families. It became universal not through market forces but through recognition that public health requires it. Vaccination programs became infrastructure.

Clean water was once a luxury good. It became universal not through market forces but through recognition that civilization requires it. Water systems became infrastructure.

The argument for AttentionDebt.org as .org rather than .com is similar: if sustained attention capacity is becoming a prerequisite for economic participation and democratic citizenship, then access to knowledge about how it develops and how to preserve it during critical windows may need to function as public infrastructure.

.com says: ”Pay us to learn how to preserve your child’s attention” (market good, creates access barrier)

.org says: ”Here’s what research suggests about critical windows and what appears to work” (public infrastructure, removes access barrier)

.com creates incentive to maintain the problem (ongoing customers require ongoing need)

.org creates incentive to solve the problem (value comes from providing useful public infrastructure)

This isn’t anti-market ideology. It’s recognition that some problems require infrastructure approaches because market incentives may not naturally align with comprehensive solution.

What Infrastructure Would Actually Mean

Public infrastructure for attention development would mean:

Clear, accessible information about critical windows Not vague advice like ”limit screen time” but specific developmental information: ”Research suggests ages 3-7 appear particularly important for sustained attention architecture formation. Ages 11-14 represent a secondary development period. Here’s what the evidence says about what matters during these windows.”

Evidence-based protocols that don’t require purchase Not apps or courses or premium programs, but actionable methods: ”Daily sustained attention activities during critical windows appear important. This can include: reading together for 20+ minutes, completing projects requiring sustained focus, having extended device-free conversations. Here are implementation approaches that work across resource levels.”

Research presented without commercial interest Not marketing disguised as science, but actual developmental neuroscience presented openly: ”Here’s what we know. Here’s what we’re uncertain about. Here’s where the research is ongoing. Here are the limitations of current understanding.”

Community knowledge sharing Not influencers selling courses, but parents and educators sharing what actually helps: ”This worked for our family. This is what we learned. Here are the resource constraints we faced and how we worked with them.”

The critical element is that none of this can be paywalled or commercialized without creating the fundamental conflict: if your business model requires ongoing customer need, you cannot have incentive to actually solve the problem.

Infrastructure must be free, open, and committed to solving the problem even though solving it eliminates the ”market.”

The Window Is Now

For the youngest Generation Alpha children, critical development windows for attention architecture are open now. What happens in the next several years may substantially affect their cognitive capabilities for life.

This isn’t meant to create panic—neural plasticity exists throughout life and improvement is always possible. But developmental neuroscience suggests these early periods matter disproportionately for foundational architecture formation.

Most families, particularly those with limited resources, don’t currently have access to clear information about these windows, what they mean, and what evidence-based approaches exist for supporting development during them.

By the time this knowledge becomes widespread—if it does—many of these windows will likely have closed for the current generation of children.

This is why infrastructure matters now rather than later. The windows are open. The stratification is forming. The longer we wait to make this information accessible, the more families miss the critical periods without knowing they were critical.

Creating Language For What We’re Observing

Much of this article has involved creating terminology for patterns that don’t yet have consensus language. Terms like ”attention debt,” ”attention bankruptcy,” ”cognitive stratification,” ”attention solvency”—these are analytical tools, not established categories.

We’re attempting to map territory that lacks good maps. The underlying phenomena—how attention develops, what environmental factors matter, how that intersects with socioeconomic stratification—are real and researchable. But the integrated framework for thinking about all of this together is still emerging.

This is important to understand: we’re not presenting established consensus. We’re proposing frameworks for thinking about patterns that may be important but are still being studied and debated.

The value of creating this language now, imperfect as it is, is that it makes patterns visible that might otherwise remain unnamed. Once you can name something, you can measure it, study it, and potentially address it.

But the language itself should remain provisional. As research improves and understanding deepens, the frameworks will need to evolve.

What This Means For Action

If any of this analysis is valid, several implications follow:

For parents: The critical windows matter more than most realize. Sustained attention activities during ages 3-7 and 11-14 may be particularly important. This doesn’t require zero screen time, but it does require regular experiences of sustained focus on single activities.

For educators: Attention capacity may be stratifying in ways that affect educational outcomes. Recognition of this pattern and access to evidence-based intervention approaches during secondary windows (early adolescence) could matter significantly.

For policymakers: If attention capacity required for democratic citizenship and economic participation is being shaped by childhood environmental conditions that correlate with socioeconomic status, this represents a structural challenge that may require infrastructure approaches.

For researchers: Better measurement frameworks, longitudinal studies, and intervention research are needed. This is understudied relative to potential importance.

For technology companies: Market incentives optimize for engagement. The developmental consequence may be fragmentation of attention during critical windows. This tension won’t resolve itself without external input.

For all of us: The stratification is happening now, during childhood, invisibly. The more visible we can make these patterns while windows are still open, the more opportunity exists for course correction.

The Infrastructure Imperative

AttentionDebt.org exists because these patterns may be too important to address solely through market mechanisms.

If sustained attention capacity is becoming increasingly valuable economically and critical for democratic participation, and if that capacity develops during specific childhood windows, and if access to developmental environments supporting formation correlates with socioeconomic status, then we may face a civilizational challenge that requires infrastructure response.

Not products. Not premium services. Not apps or courses or programs.

Infrastructure. Free. Open. Committed to making knowledge accessible regardless of ability to pay.

The attention divide may be becoming a class advantage. If so, preventing it from becoming increasingly difficult to reverse requires infrastructure now, while critical windows remain open for the current generation.

That’s why it must be .org.

That’s why it must be free.

That’s why this matters now.

The windows are open. The stratification is forming. The choice is whether to build infrastructure while there’s still time to make a difference.

Time to build what’s needed before the windows close.

Acknowledgment of Uncertainty

This article synthesizes research from developmental neuroscience, education research, economics, and sociology. The individual findings are grounded in peer-reviewed research. The integrated framework connecting them is more speculative and should be read as hypothesis and analysis rather than established fact.

Critical windows exist—that’s well-established in developmental neuroscience. Whether attention architecture specifically follows the patterns described here is still being researched. The socioeconomic stratification of developmental environments is documented. Whether this creates lasting cognitive differences in the ways described here requires more longitudinal research.

The purpose is not to make definitive claims but to make patterns visible so they can be studied, discussed, and potentially addressed while developmental windows remain open for current generations.

We’re creating maps of territory we’re still exploring. The maps will improve with time and research. But having imperfect maps now may be better than waiting for perfect ones while critical windows close.

Rights and Usage

All materials published under AttentionDebt.org — including definitions, methodological frameworks, data standards, and research essays — are released under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

This license guarantees three permanent rights:

- Right to Reproduce

Anyone may copy, quote, translate, or redistribute this material freely, with attribution to AttentionDebt.org.

How to attribute:

- For articles/publications: ”Source: AttentionDebt.org”

- For academic citations: ”AttentionDebt.org (2025). [Title]. Retrieved from https://attentiondebt.org”

- For social media/informal use: ”via @AttentionDebt” or link to AttentionDebt.org

Attribution must be visible and unambiguous. The goal is not legal compliance — it’s ensuring others can find the original source and full context.

- Right to Adapt

Derivative works — academic, journalistic, or artistic — are explicitly encouraged, as long as they remain open under the same license.

- Right to Defend the Definition

Any party may publicly reference this manifesto and license to prevent private appropriation, trademarking, or paywalling of the term attention debt.

The license itself is a tool of collective defense.

No exclusive licenses will ever be granted. No commercial entity may claim proprietary rights, exclusive data access, or representational ownership of attention debt.

Definitions are public domain of cognition — not intellectual property.