You are the biological parent.

The platform is the legal guardian of your child’s digital identity.

Not metaphorically. Structurally. According to the contract you agreed to when you—or your child—created that account.

You think you have custody because you’re the parent. You feed them, house them, make medical decisions, choose their school. Legal custody over their physical body and life decisions belongs to you.

But their digital self—their identity representation, their relationships, their content, their behavioral data, their attention patterns, their developing preferences—exists under different custody terms.

And those terms don’t grant you guardianship. They grant it to the platform.

This isn’t an accusation. This is contract analysis. The Terms of Service are public. The custody structure is documented. The inversion is measurable.

What’s remarkable isn’t that this arrangement exists. What’s remarkable is that most parents don’t realize they agreed to it.

A Note on Precision

This analysis concerns legal and structural relationships governing digital identity systems. It examines who has decision-making authority over data, identity representation, and access rights for minors in digital spaces.

This is not a claim about parental capacity or love. Your relationship with your child—psychological, emotional, developmental—remains entirely yours. This analysis addresses only the legal architecture governing digital custody: who controls what, who decides what, and who can revoke what.

Terminology: In this essay, terms like ”custody” and ”guardian” describe functional, contractual control over accounts and identity representations, not formal family-law designations.

The goal is transparency about existing contractual structures, not judgment about parenting choices.

Clarification: References to ”platforms,” ”contracts,” or ”Terms of Service” throughout this essay are generalized descriptions of common industry practices and do not quote or refer to any specific company or service provider.

Jurisdiction: Age thresholds, parental consent rules, and platform liability regimes vary by country and over time (e.g., GDPR Art. 8 allows a 13–16 range). The analysis here addresses common industry structures, not any single legal system.

The Custody Question Nobody Asked

Here’s a question most parents have never considered:

Who has legal custody of your child’s digital identity?

Not their physical body. Not their education. Not their healthcare. Their digital self—the representation that exists in apps, platforms, games, social networks.

The answer depends on what ”custody” actually means. And the legal definitions reveal something most parents find shocking:

In physical space, you have custody.

In digital space, the platform does.

Let’s be precise about this.

Legal Definitions: Custody, Guardianship, Ownership

In family law, these terms have specific meanings:

Custody = legal authority to make decisions about the child’s welfare, residence, and care.

Guardianship = responsibility for managing the child’s affairs when parents cannot or when specific domains require designated authority.

Ownership = property rights over assets, which cannot apply to persons but can apply to their data and digital representations.

For your child’s physical existence:

- You have custody (decision-making authority over their welfare)

- You are their guardian (responsible for managing their affairs)

- You have ownership of nothing regarding the child themselves (children are not property), but you have parental rights

For your child’s digital existence:

- The platform has custody (decision-making authority over their identity representation)

- The platform is the guardian (manages the account, data, access)

- The platform has ownership of the data infrastructure and asserts property rights over the account itself

This isn’t speculation. This is what the contracts say.

What Terms of Service Commonly Grant

Most platforms with users under 18 have Terms of Service that include language like this (paraphrased from common clauses):

On Account Ownership:

”You may not transfer, assign, or sell your account. The account and all associated data remain the property of [Platform].”

Translation: The account isn’t your child’s property. It’s the platform’s property, which your child is permitted to access.

On Data Rights:

”You grant [Platform] a worldwide, royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable license to use, store, modify, and distribute any content, data, or information associated with your account.”

Translation: Everything your child creates, posts, or generates through usage does not transfer your child’s copyright, but typically grants the platform a broad, often perpetual or long-term, license to use and process the content and related data.

On Access Control:

”[Platform] reserves the right to suspend or terminate accounts at our sole discretion, with or without cause, with or without notice.”

Translation: The platform can revoke your child’s access instantly, without explanation, without appeal.

On Parental Rights:

”For users under 13, we require verifiable parental consent. For users 13-17, we recommend parental involvement but do not require oversight for account operation.”

Translation: Once your child turns 13, the platform relationship supersedes your oversight. You have no access rights unless your child grants them.

On Data Portability:

”You may request a copy of your data. However, data export may not include relationship graphs, engagement metrics, or algorithmic reputation signals, as these are derived platform assets.”

Translation: Your child cannot take their social graph, reputation, or identity representation when they leave. Those remain with the platform.

Now let’s map this against actual custody rights:

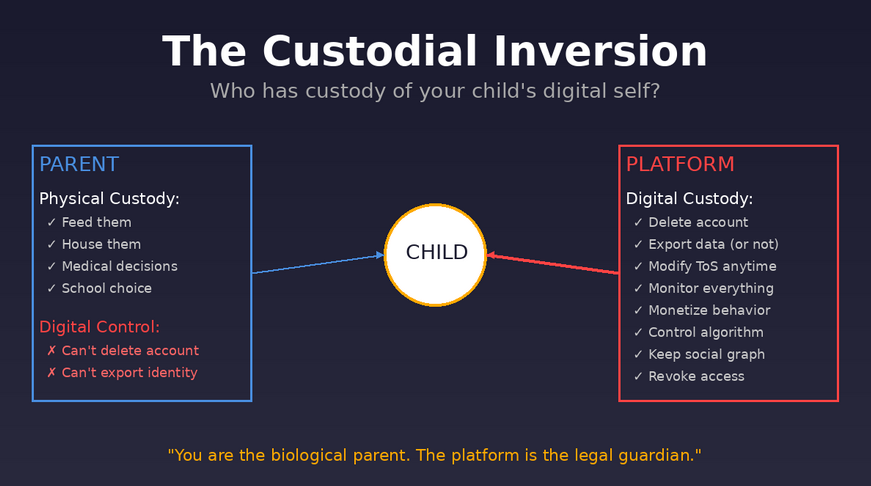

The Custody Comparison: Parent vs Platform

Let’s examine who actually controls what:

Can delete the account:

- Parent: No (unless child is under 13 and parent has access credentials)

- Platform: Yes (unilaterally, immediately, without appeal)

Can export the identity:

- Parent: No

- Platform: No (they refuse portability)

- Result: Nobody can take the digital identity elsewhere

Can modify terms of access:

- Parent: No (cannot change ToS)

- Platform: Yes (can change ToS unilaterally, retroactively)

Can monitor behavior:

- Parent: Only with child’s consent (for 13+) or if you have physical access to device

- Platform: Continuously, comprehensively, permanently

Can monetize the data:

- Parent: No

- Platform: Yes (directly through advertising and data licensing)

Can transfer the identity to another service:

- Parent: No

- Platform: No (they prohibit transfer)

- Result: The identity is captive

Can determine what content the child sees:

- Parent: No (algorithm decides)

- Platform: Yes (algorithmic curation is proprietary)

Can permanently preserve the data:

- Parent: No (platform can delete)

- Platform: Yes (perpetual license)

Can revoke access if child violates rules:

- Parent: Theoretically yes (can take away device), but cannot revoke the account

- Platform: Yes (can delete account permanently)

Look at that list carefully.

In every category involving control, access, modification, or deletion—the platform has more authority than the parent.

The parent has physical custody of the child.

The platform has digital custody of the child’s identity.

This is the custodial inversion.

Why This Isn’t About Platform Evil

Before anyone misunderstands: this is not about platforms being malicious.

This is about legal architecture that evolved to solve one problem (enable service provision) but created an unexamined side effect: parents surrendered digital custody without realizing custody had been transferred.

Platforms didn’t set out to become legal guardians of children’s digital selves. They set out to provide services and needed terms that allowed them to operate, moderate, and monetize.

But the resulting structure inverted custody in ways that weren’t advertised, weren’t debated, and weren’t chosen consciously by parents.

The contract says: ”You grant us these rights.” Most parents think that means access rights. It actually means custody transfer.

The Neural Custody Layer: Who’s Raising Your Child’s Attention?

Now let’s add the biological dimension.

Your child’s brain is being shaped by patterns of attention, reward, and interaction. This is neuroplasticity—the brain physically rewires based on repeated experience.

Neural development during childhood and adolescence is extraordinarily sensitive to environmental inputs. The patterns that get reinforced become the architecture that persists.

So here’s the uncomfortable question: Who is actually parenting your child’s attention development?

Let’s quantify:

Average daily parent-child conversation time (ages 10-17):

Approximately 25-40 minutes of meaningful dialogue per day (studies vary, but most converge around 30 minutes).

Average daily screen time on social/gaming platforms (ages 10-17):

Approximately 4-7 hours per day (again, studies vary, but median is around 5.5 hours).

That’s a 10:1 ratio or higher. For every minute of parent-directed attention shaping, there are 10+ minutes of algorithm-directed attention shaping.

The algorithm is not neutral. It’s optimized. Optimized for engagement, which means optimized to capture and retain attention through mechanisms that trigger dopamine responses: unpredictability, social validation, novelty, and variable reward schedules.

These are the exact mechanisms that train attention patterns.

So structurally, the question becomes unavoidable:

Who is the primary environmental influence shaping your child’s attentional habits, reward expectations, and behavioral patterns during their most neuroplastic years?

The biological answer is: whoever controls the majority of their attention hours. And that’s not the parent. That’s the algorithm.

The legal structure enables this: the platform has custody of the identity, access, and behavioral data. The platform designs the reward systems. The platform decides what content appears. The platform optimizes for engagement.

The parent has no override. No ability to modify the algorithm. No way to export the relationship and take it to a healthier environment. No structural authority over the system shaping their child’s cognitive development.

You are the biological parent. The algorithm is the behavioral co-parent. And the algorithm has more hours.

This is neural custody. And it’s governed by the same Terms of Service that inverted legal custody.

The Regulatory Gap: Why Toys Have Rules and Apps Don’t

Here’s where the inversion becomes absurd:

Physical toys that affect children’s development are heavily regulated.

Digital apps that affect children’s development are essentially unregulated.

Let’s compare:

Physical toys (regulated under consumer safety laws):

- Must pass safety testing before sale

- Cannot contain lead, toxic materials, or choking hazards

- Must have age-appropriate warnings

- Can be recalled if found harmful

- Manufacturers have liability for harm

- Parental oversight is assumed and protected

Digital apps (minimally regulated):

- No pre-market safety testing for psychological impact

- Can contain addictive design patterns, manipulative UX, or harmful content with minimal restriction

- Age gates are self-reported and unenforced

- Cannot be ”recalled” even if proven harmful (user must delete voluntarily)

- Platforms have liability shields (Section 230 in the US)

- Parental oversight is contractually limited after age 13

Same mechanism: shaping a child’s behavior and development.

Different rules.

If an app did what it does but was a physical toy, it would be illegal.

Because it’s an app, it’s legal.

Why?

Because regulation was written for physical products. Digital products exploited the gap. And by the time the gap was visible, millions of children were already using platforms under terms that had inverted custody.

The toy industry is heavily regulated because physical harm is visible and immediate. Neural harm is invisible and delayed. By the time the impact is measurable, the custody inversion is already complete.

The Actionable Question: What Should Change?

This analysis is not nihilistic. Structural problems have structural solutions.

If custody has been inverted through contract, it can be re-inverted through architecture.

Here’s what that would require:

1. Guardian Override Rights

Parents should have structural authority to:

- Set attention budgets that the platform must enforce

- Override algorithmic recommendations with family-defined value profiles

- Export identity and relationships if they choose to move platforms

- Access transparency into what the algorithm is showing and why

This isn’t surveillance. This is parental custody restored at the architectural level.

2. Portable Identity for Minors

Children’s digital identities should be portable from the start:

- Usernames, relationships, and reputation should export with cryptographic verification

- No platform should be able to hold a child’s accumulated social capital hostage

- Switching platforms should not mean social death

This makes platforms compete on value rather than lock-in.

3. Algorithmic Transparency Protocol

Parents should have access to:

- What variables determine what their child sees

- How the recommendation system is optimizing

- What behaviors are being reinforced through design

Not to control every decision, but to understand the system co-parenting their child’s attention.

4. Age-Appropriate Custody Transfer

The current cliff at age 13 (when parental consent is no longer required in most jurisdictions) is arbitrary:

- A 13-year-old is not developmentally equipped to read and understand Terms of Service

- A 13-year-old does not have legal capacity to enter binding contracts in most contexts

- But platforms treat 13 as the age of digital majority

Custody transfer should be gradual, transparent, and developmentally appropriate. Not a binary switch that strips parental authority overnight.

5. Harm Accountability

If toys can be recalled for causing harm, apps should face similar accountability:

- Independent testing for addictive design patterns

- Liability for demonstrable developmental harm

- Mandatory design standards for platforms serving minors

Not censorship. Safety standards. Like we have for every other product that affects children.

The Unanswered Question

Here’s the question this analysis leaves unanswered—intentionally:

Should parents have custody of their children’s digital identities, or should platforms?

This isn’t a question with an obvious answer. It’s a question that hasn’t been asked clearly enough to debate seriously.

Some will argue platforms need authority to moderate, to ensure safety, to prevent abuse. This is valid.

Some will argue parents need authority to protect development, to enforce values, to prevent exploitation. This is also valid.

The problem isn’t that one side is right. The problem is that the question was never posed. Custody was inverted quietly, through contract terms most parents never read, governing systems most parents don’t understand.

You cannot have informed consent without informed choice. And you cannot have informed choice without asking the question.

So here it is, clearly:

Who should have legal custody of your child’s digital self?

- Their name

- Their relationships

- Their reputation

- Their content

- Their attention patterns

- Their behavioral data

- Their developing identity

Should that custody belong to the biological parent, the platform, or some hybrid structure that hasn’t been designed yet?

This analysis doesn’t answer that question. It just makes the question unavoidable.

Because right now, the answer is: the platform has custody, and most parents don’t know they transferred it.

And that answer was never chosen. It was defaulted into.

The Closing Observation

The Terms of Service are public documents. The custody structure is legally documented. The time-ratio is measurable. The neuroplasticity is scientific consensus.

Nothing in this analysis is speculative. It’s just rarely compiled into a single question:

Who has custody of your child’s digital self?

The law says: the biological parent has custody of the child.

The contract says: the platform has custody of the account.

The biology says: whoever controls the attention hours shapes the development.

And the uncomfortable truth is: all three of these point to the platform, not the parent.

Not because platforms took custody through force.

Because parents transferred custody through contracts they didn’t read governing systems they didn’t understand with consequences that weren’t explained.

The inversion happened quietly. The reversal will require intention.

This is not a call to delete accounts. This is not a claim that platforms are evil. This is not parenting advice.

This is structural analysis.

If you can be deleted, you are not sovereign.

If your child can be deleted, someone else has custody.

And if that someone else is a corporation optimizing for engagement during your child’s most neuroplastic years—well, that’s not an accusation.

That’s just what the contract says.

Read the Terms. Map the custody. Ask the question.

Then decide if the answer you discover is the answer you would have chosen.

Rights and Usage

All materials published under AttentionDebt.org—including definitions, methodological frameworks, data standards, and research essays—are released under Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

This license guarantees three permanent rights:

Right to Reproduce: Anyone may copy, quote, translate, or redistribute this material freely, with attribution to AttentionDebt.org.

Right to Adapt: Derivative works—academic, journalistic, or artistic—are explicitly encouraged, as long as they remain open under the same license.

Right to Defend the Definition: Any party may publicly reference this manifesto and license to prevent private appropriation, trademarking, or paywalling of the terms ”Custodial Inversion,” ”Neural Custody,” ”Guardian Override Rights,” or related concepts defined herein.

The license itself is a tool of collective defense.

No exclusive licenses will ever be granted. No commercial entity may claim proprietary rights, exclusive data access, or representational ownership of these concepts.

Definitions are public domain of cognition—not intellectual property.